Part 3. In Praise of the Passive Voice: Effacing the Subject to Showcase the Object

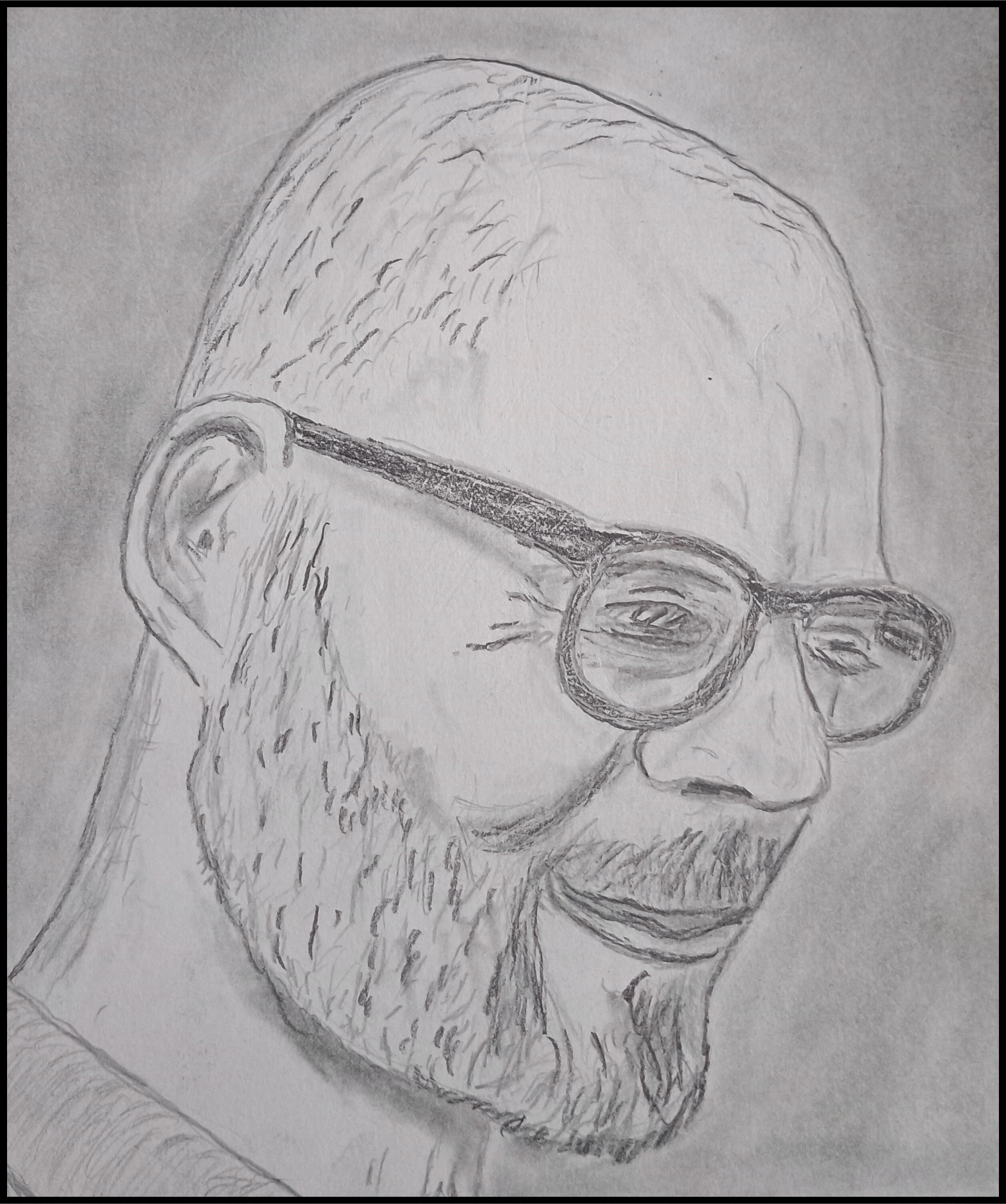

- Paul Carlucci

- 3 days ago

- 5 min read

Updated: 2 days ago

This is the final post of a three-part series. Part one is available here, and part two is available here.

Now that you’ve learned what the passive voice is and isn’t, we can talk about when you might want to use it and why.

For guidance, there are loads of instructive cliches you can turn to online (e.g., when politicians note that “mistakes were made”). For something more official, language and style authorities can help, and we’ll explore a couple at the end of this post.

But the short of it is pretty straightforward. Often enough, the subject of a sentence just doesn’t matter enough to merit the helm; instead, it’s the object you want out front. Let’s have a look at two contexts, one in creative writing and the other in academia.

The Passive Voice in Creative Writing

The example we’ve been using throughout this series—“The pickle was eaten” or “The pickle was eaten by Timmy”—is, at first glance, one of those hideous sentences that swiftly delivers the passive unto the opprobrium in which it’s so widely held. I mean, ugh, just look at that mess: so wordy, so awkward, so vague.

But what if that sentence appeared in a paragraph resolutely focused on the pickle? Remember how, in part one, I described it as “perfectly firm,” an object of desire that Timmy had been storing for later enjoyment, eventually crunching it in public after a gruelling shift at work? What if our paragraph explored the pickle’s day-long experience in the front pouch of Timmy’s murse? We might see the following:

It was dark in the murse, and the world pressed in from outside, threatening. Slipped into a plastic baggy earlier that morning, the pickle wasn’t at risk of drying out, but it longed for the briny bath of its jar, where its warty cousins still floated in their post-cucumber oblivion, blind to the cruelties of the broader world.

A paragraph like this, sketching the pickle’s life experience with multiple active constructions, would validate a passive-voice closer exactly like our example, wouldn’t it? Because in the end, the pickle was eaten, and we now care more about the pickle than we do the person who ate it, really just a ruinous digestive tract by this point.

In this context, fronting a sentence with “Timmy” would throw our attention off the pickle, and because we don’t have an ergative option (“to eat” won’t tolerate its direct object assuming the life force of its subject), the passive is the far better choice.

The Passive Voice in Academic Writing

For academic writers, this pickled silliness may feel too abstract to use, but fear not. Most of you encounter similar but more grounded situations in your methodologies, and in my experience editing your work, you instinctively use the passive voice, offering clauses like “Themes were identified,” “Categories were coded,” and “NVivo was used.”

Your instincts are serving you well, but what to make of life when you’re told, often with withering contempt, that the passive voice is unbecoming and you don’t know what you’re doing?

Before referring to the authorities, let’s first imagine what would happen if you used active constructions instead. Most academic styles permit the first person these days, so you could write clauses like “I identified themes,” “I coded categories,” and “I used NVivo,” and even if you’re working with guidelines that don’t permit first person, you could replace the pronouns with “this researcher.”

But if you’ve got a lot of steps in your methodology, the repetitive word choices will make your writing feel first very choppy and then very blurry. Slowly, your reader will become annoyed without quite knowing why, and their attention will drift.

Plus, what if you’re not the only author involved in the methodology? If you’re using first person pronouns, which are inherently intimate, it’d be weird to write “a second researcher coded,” but weirder still would be “Malcolm Erics coded.” Does anyone care enough to check the bylines to see who Malcolm is, and are you sure you want your reader breaking off engagement to do something so pointless? Meanwhile, if you’re using third person, should the reader really be burdened with keeping track of the first, second, and subsequent researchers?

The answer to these questions is a resounding no. The passive voice is perfectly appropriate for methodologies not only because it keeps the focus on the steps and not who did them but also because it just sounds infinitely better. And sounding better, according to usage guru Bryan Garner, is validation enough.

What the Authorities Say

Garner is the grammar and usage mastermind behind Garner’s Modern English Usage and the grammar, syntax, and word usage sections in The Chicago Manual of Style. He’s kind of a big deal. In the former volume, he offers an essay of a few pages on this very topic, and he lists six good reasons for using the passive voice:

the subject doesn’t matter;

the subject is unknown;

you want or need to hide the subject’s identity;

you want to put an important word at the end of the construction, this word being your subject;

you want to focus on the object; and

and the passive just sounds better.

In the section on verbs in The Chicago Manual of Style, he comes across a little less allowing, saying that the passive “is typically, though not always, inferior to the active voice.” He goes on to note that it’s a matter of perspective, using a cat-and-mouse example in place of our Timmy-and-pickle motif.

For academic writers looking for guidance a little closer to home, APA can save the day. Support can be found here on the organization’s website, where it says that the passive voice is useful when you want to elevate the recipient of an action over the actor, but note that the language here is a little washy, almost reminding us of an indirect object, which receives the direct object (e.g., “John gave me the book”). If you really want to make your case, you should say you want to elevate the thing being acted on or the thing receiving the thing being acted on.

A Matter of Politics, not Knowledge

How fiercely you push back will probably have a political dimension. If you get the feedback in an aggressively withering tone, trotting out everything you learned in this series probably won’t help, although you might try a nudge or two to see if humility is indeed totally absent from this person’s psyche. Meanwhile, if you have a well-meaning but mistaken editor, they’ll probably welcome the education.

What counts most is that you yourself know what’s going on. That way, you won’t over-police others when you end up in the editor’s chair. Instead, you can promote some of the language’s more subtle aspects, making better, more conscientious writers of everyone you work with.

Comments